In 1960 a man from Edgware was cross. So cross in fact that he wrote to The Times. Under the title ‘Mammoths of the Tube’ he outlined the reasons for his sudden burst of outrage;

‘Sir – One complains of the congested conditions prevailing today on the London Underground Railway system. Lately his condition seems to have been aggravated by various females carrying baskets, bags, and other articles which appear to me, a lay male, grossly oversized. These baskets would bring disgrace on a pack donkey.’

He demanded these items be prohibited. This letter is fascinating in certain respects. Firstly, it is one of those rare examples of an article that manages to conflate mammoths, a large prehistoric mammal, with handbags, which are neither prehistoric or mammals. Secondly, it underlines how certain groups on the London Underground have often been picked on by the rest.

“The rest” have usually been the male middle-class commuters. In my own Ph.D. work they (or the management on their behalf) usually pick on the male working-class passengers (who are invariably presented as a smoking, spitting, dirty, drunken hoard of menace bringing horror to everyday travel). But a quick look through the newspapers of yesteryear revealed another target; ladies.

I use the term ladies specifically. “Women” was a term typically applied to third-class working-class passengers (who were also referred to as work-women like their male counterparts were workmen). “Ladies”, however, usually referred to middle or upper-class individuals who travelled second and first-class. Complaints about working-class female passengers seem rather muted (in comparison to working-class men and middle-class women), but perhaps this is because they rarely shared the second and first class carriages with the male middle-class commuters so keen on writing off to The Times.

The initial problem seems to have emerged from the complicated system in force on Metropolitan trains from the 1860s. Not only were trains divided into three classes, but there was the added complication that certain carriages were smoking and non-smoking and briefly in 1874 – 5 some carriages were ‘Ladies only’.

The ‘Ladies only’ carriages unsurprisingly provoked waves of outrage. Typically they were empty, which during the rush hours raised the ire of many a male commuter trying to force his way into an overcrowded carriage. But perhaps more irritating for the lone commuting male was the idea that a lady could take a man onto the carriage ‘under her protection’, permitting husbands to travel with wives. The perceived double standard fed the anger, with one gentleman writing angrily that the ‘protection’ system was ridiculous and that lone married men and clergymen should be allowed on the carriages as well (presumably because they theoretically presented none of the dangers of single men). The ‘Ladies only’ restrictions soon disappeared.

In 1891 the periodical Moonshine published a short piece entitled ‘what you ought to do (if a lady on the Underground) – by one who knows’. It presents the lady passenger as utterly incompetent, beginning with ‘on presenting yourself at the booking office, be careful to reach the window from the wrong direction, and be the more careful to do this at stations where directions are painted up largely and plainly’. But the article, not a particularly inspired attempt at humour, reveals the main point of contention between male and female passengers – smoking.

Smoking had been banned by the Metropolitan Railway when it had opened in 1863. But, despite the numerous complaints about the sulphurous atmosphere the steam worked railway generated (indeed, to the extent the smoky atmosphere was killing people), the smoking lobby became increasingly vociferous about passengers being allowed to smoke on the system. By 1874 the Metropolitan and the slightly younger District Railway acceded to the demands (and legal obligation) and provided separate smoking carriages.

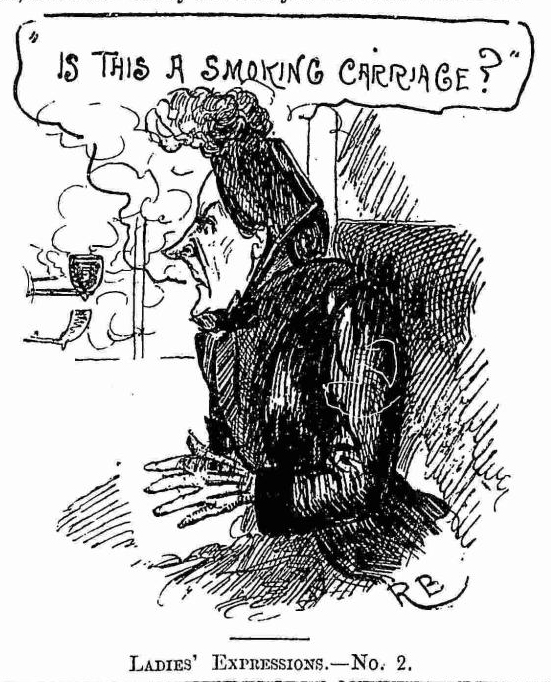

To the male passenger tucked up with a newspaper and a pipe in a smoking compartment nothing appears to have been worse than the arrival of a lady. Moonshine outlined that the lady passenger should ‘eventually dive into a first class [carriage], but be especially careful it is a “smoker.” Don’t discover the fact until the train is in motion, and then cough and choke in an alarming manner. Continue this until you have every pipe extinguished, and both windows open, and then get out at the next station.’

Smoking carriages were effectively a male space, ultimately because smoking was an activity largely restricted in public to men. This is perhaps why in the early 1920s the idea of the female ‘flapper’, a woman who showed apparent disdain at established social conventions, was often linked to the individual to being a public smoker, as this little 1922 cartoon depicts (along with what was clearly on the minds of certain repressed gentlemen).

Moreover, the carriages on the Metropolitan and District were compartmentalised (divided into sections), which meant passengers were sat in close and confined company with each other. It was seemingly felt that if a lady was present in the compartment then the men were usually obliged to stop smoking. Notably it was the First Class carriages which were the main setting of these complaints, reinforcing the idea that it was middle and upper-class men taking issue with women of the same social class.

The smoking issue appears to have been less of a problem on the tube railways, where carriages were open (you can walk up and down the whole carriage) and there were no class divisions. But on the Tubes there was apparently a bigger problem that women were bringing into the Underground; hat pins.

In 1914, a gentleman under the pseudonym ‘One for all’ complained bitterly to The Times about what was termed ‘A constant menace in the Underground’. He wrote;

‘Last night I entered the tube lift at the Post Office station [now St Pauls], just at the time when the crush of the people homewards bound is at its height. I saw two young girls entering the lift just in front of me, both wearing two or three hat pins protruding about three or four inches. While I was still contemplating on the very evident danger and trying in a pure sense of self-preservation not to come into touch with these uninviting necessities of the otherwise attractive toilette of the women of to-day, one of the young ladies moved, in conversation with her friend, her head to one side and one of her hat pins went right into the eye of a gentleman standing next to me.’

The incident was hardly isolated. Three weeks earlier a lady had been fined £3 through the Law Courts for inadvertently scratching another lady in the face with a hat pin. ‘One for all’ painted a scene of daily terror for passengers on the tube as hat pins waved maliciously about threatening to ‘give you a little souvenir’, and pointed out that on the London County Council’s tramways such was the perceived danger that signs were put up inside tramcars urging ladies to wear protected hat pins.

Notably the complaints regarding female passengers sent into the papers almost disappeared after the Great War. On my own brief survey of the newspapers, the only complaint subsequent to the 1914 hat pins is the 1960s ‘Mammoths of the tube’, which appears more the rant of one particular male suburbanite than a widespread issue. Perhaps the ebbing away of the complaints was largely due to women becoming an increasingly large presence on the Underground during and after the Great War, as the trailer for the 1928 film Underground suggests.

Women had been a minority on the Underground before the Great War; their presence was new and provoked comment because it was new. A similar issue arose with male working-class commuters, a group who also were complained about bitterly before 1914 when their travelling was something of a novelty. But both groups rarely gained such overt criticism after 1918, when complaints usually focused on the fact that everyone, women, men, working class, and middle class were all being squashed together during the rush hour.

Perhaps they also found someone else to pick on. For the regular Underground users of today (of all sexes, classes, and races) it’s often the utterly perplexed American tourist stuck at the ticket barrier gazing deeply into their Oyster card as if the card itself will suddenly perk up and inform the holder how it all works. Clearly a problem so bad they had to make this bewildering advice video.

But it wasn’t all stereotyping before 1914, as this piece from an 1894 article entitled ‘a lady to the rescue’ shows;

‘The lady in the smoking compartment has again come to the front. A smoker who entered a first class carriage on the Underground railway found himself joined by a young lady just as the train was moving off. Half afraid of the answer, he asked her if she objected to smoking. “Not at all” was the reply, and, the smoker placing his Havannah between his teeth, he produced his matchbox. Alas, it was empty! He had resigned himself to a smokeless journey, when, to his surprise, she handed him a dainty little sliver case well stocked with vestas.’

Lots of interesting parallels between the “mammoths” and the tourists who are currently the pet hate of many regular Tube commuters. Lack of familiarity with the Tube (which tends to slow you, and therefore others, down) is one- I imagine women on shopping trips would use the Tube less than commuters.

The other one, of course, is the packages. You still get letters in the Metro complaining about people with luggage on the Tube, especially if it’s at rush hour and/or is a backpack.

Pingback: Pipe up | The Pirate Omnibus