One of the problems with being a historian is that every time you see the phrase ‘revolutionary thinking’ there’s a jaded sounding little voice in your head that sarcastically says really? So when the Londonist opened an article with the following line my reaction was fairly cynical:

‘How’s this for revolutionary thinking: the Green Party is proposing abolishing fare zones across London, for one flat fare, wherever you want to travel.’

Why was I dubious? Because I’m looking at a Royal Commission from 1937 and the topic is: flat rate fares for the whole of London. In fact, we can go even further back to the 1870s to find other flat rates in operation. If you’re one of those commuters on the Enfield Town – Liverpool Street line you’ll be pleased/outraged to know that up until the Great War you could travel to central London for a mere two penny daily return from any station along the line, so long as you travelled before 6.30am. ‘The cheapest railway in the world’ they used to call it.

But 1937 is the year worth focusing on. This was when Frank Pick, Vice Chairman of the London Passenger Transport Board (usually called London Transport) was questioned on whether London should operate a system of flat rate fares. At the time New York offered a flat rate fare of 5 cents over their metro system, and Pick was now under pressure to explain why London couldn’t do the same. His main counter argument was a financial one, pointing out that New York subsidised its transport network heavily because of the low fares, while London Transport broadly broke even. This argument is not so applicable today. In 1937 94.8 per cent of London Transport’s income came from fares. Currently only 40.0 per cent of Transport for London’s income comes from fares (from the figures presented by the Green Party). With the transport network far more subsidised today the notion of financial restraint is fairly moot. Furthermore, let’s accept the Green’s contention that the flat rate will not sink Transport for London’s budget, and that they’ll make up any deficit elsewhere. There is, however, a much bigger problem. One that Pick flagged up immediately, but which the Greens don’t seem to mention. Rents.

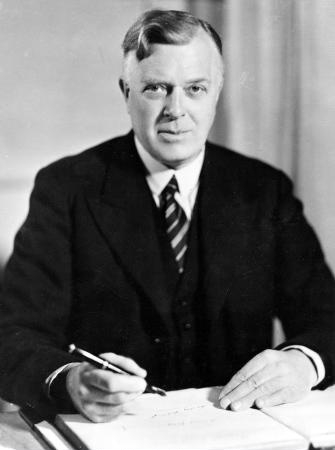

Frank Pick, possibly thinking about rents, via wikimedia commons.

We would all love to have cheaper transport. I currently live out in Zone 5. Cheaper transport would be amazing for me. But transport and housing interact like a one-way see-saw. If you push transport costs down, rents usually rise. As Pick explained almost 80 years ago:

‘It is very simple. In New York what happens is that you can develop intensively an area in the Bronx, a long way from New York, and you can raise tremendously high ground rents because you know you can fill that area with people who must live out there, knowing that they can get to their work at this flat rate of 5 cents, that is to say, what you are doing is to put more money into the hands of the ground landlords.’

Last year Thrillist made an excellent Tube Rent Map. For the most part (there are obviously exceptions) rents decrease as the distance from the centre of London increases. This is because the cost of transport is higher, making housing in these areas far less attractive to renters: a cheaper rent offsets the cost of transport. But a flat rate fare removes that disadvantage. While those living further away still suffer a “time disadvantage” (you sit on a train for longer every day which can be quite irritating unless you’re using the time to read The One Hundred Year Old Man who climbed out the window and disappeared) the monetary disadvantage disappears.

Suddenly outer areas would become far more attractive to private landlords and developers. Demand for housing in outer areas would shoot up because rents and transport are both cheap, but as demand for housing increases and transport costs remain capped, rents simply go up. The idea of the Green’s ‘one zone’ is to make life better for low-paid workers forced into outer areas (which is presumably because rents are cheaper). The end result could be the exact opposite, with rents in these areas soaring in the long run. Furthermore, because the housing crisis is so severe the demand for housing is unlikely to be met, so there is unlikely to be any fall in rents thereafter. The eventual winners would simple be private landlords hiking up rents and private developers setting higher prices for outer-London housing.

The idea of cheap transport is laudable, but the Green’s policy isn’t connected enough with other factors in the metropolis: particularly housing. The idea of the ‘single zone’ appears to be a silver bullet, but as with all silver bullets they tend to be more wrapped in myth than reality. To make the system work there would have to be a commitment to actually solving the housing crisis, and, in all likelihood, rent control.

Call me a cynic, or a historian, but neither seem likely any time soon.

Sources:

http://londonist.com/2016/01/no-more-zones

http://www.timeout.com/london/blog/this-tube-map-shows-the-average-rent-costs-near-every-underground-station-092915

http://www.sianberry.london/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/FaresBriefingJan2016LondonGreenParty_FINAL.pdf