Rush hour. For some it’s an 80’s classic by Jane Wiedlin featuring a bizarre array of dolphins for no apparent reason. For others it’s Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker belting their way through two fun action comedies. Also a third action comedy which we don’t speak of. Ever. For millions of people though rush hour is the sequence of events where you attempt, in a sort of live action version of Marioland, to fight your way from home to work in the morning. It’s also a problem that, in London especially, is getting worse. Though we’re probably better off than in Japan, where a team of half a dozen station officials lovingly shove you into a carriage.

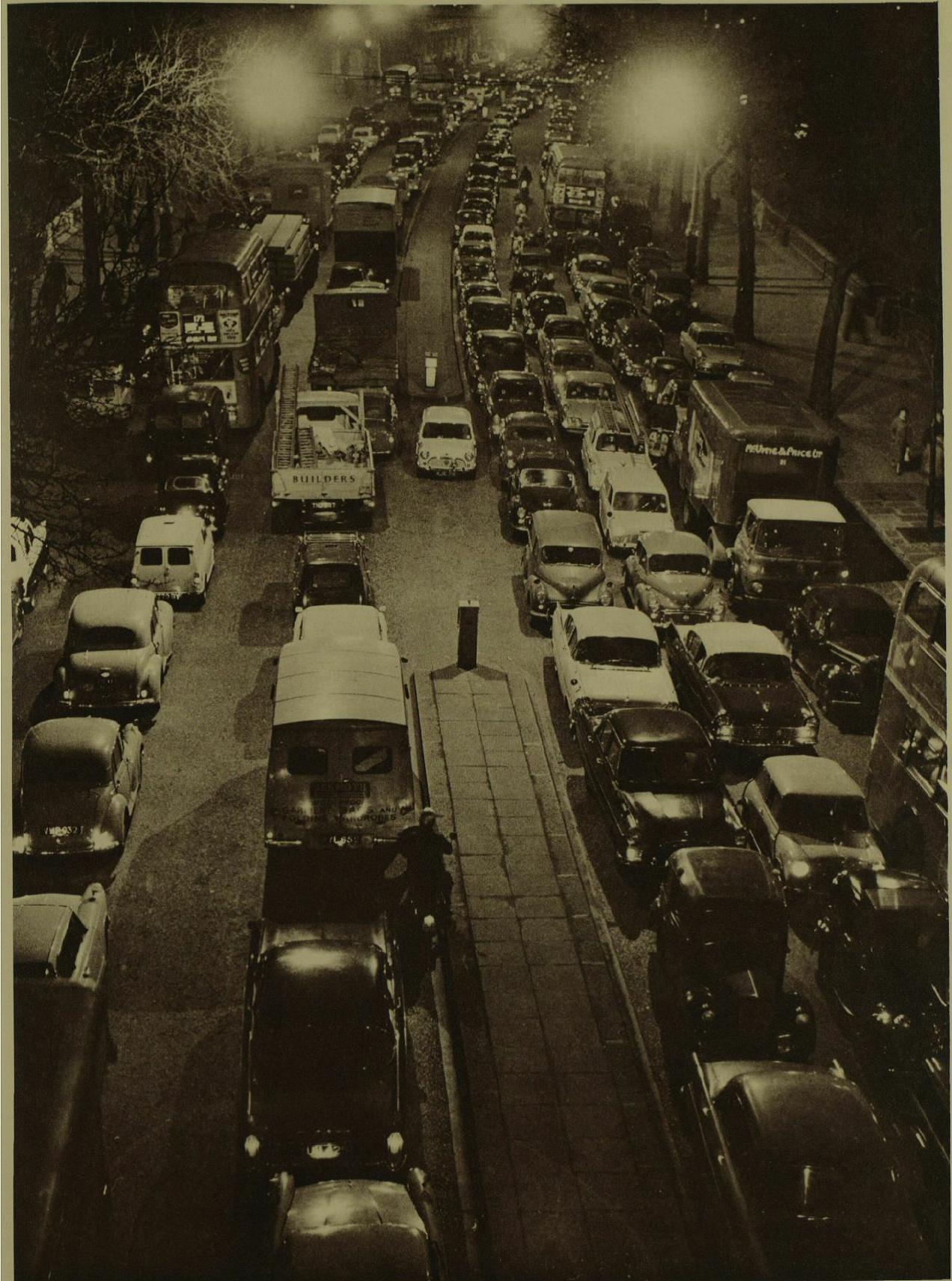

How to deal with rush hour isn’t a new question. Congestion on the streets of London was horrendous in the nineteenth century as Gustav Dore depicted in 1872’s London: A pilgrimage.

Ludgate Hill in 1872, from Wikimedia Commons.

The solution then was to go underground. The Metropolitan Railway first started running in 1863 and the first tube, the City & South London, got going in 1890. The problem was these tended to encourage more passengers, and combined with both a growth of population and the number of journeys people were taking, failed to provide enough capacity. By 1913 the underground railways were beginning to fill up, leading one man to complain that on the District Line ‘…the train is literally crammed with people standing crushed together from one end of the train to the other, huddled together little better than animals…’ By 1919, with the huge increase in passengers that the Great War created the situation was so bad a Government Select Committee decried that

‘Trains were crowded not merely to excess, but almost to danger point. The crush in the “peak hours” not only overloaded public conveyances, but subjected travellers, particularly the old, the feeble and women, to an amount of suffering, the effects of which often unfitted them temporarily for their ordinary duties.’

By 1970 the rush hour was so bad the transport system had developed a bizarre electronica noise that bombarded passengers as they travelled and the situation has hardly improved since. In recent years a host of upgrades have tried to solve the problem. Crossrail is liable to be the most successful, but creations such as the Emirates Cable Car have been about as much use as, well, a cable car in the middle of nowhere serving absolutely no-one. Seriously? That’s the plan? A cable car? So what I’m going to do here is line up a few solutions to the London rush hour inspired by the last 200 odd years for your perusal. How do we solve the rush hour? Well let’s try:

Bigger trains

Obvious right? Just have bigger trains. The problem is that most of the railway architecture in Britain was designed in the 19th Century. As such, the space around the track (so the size of tunnels, bridges, platforms, etc.) is limited, as it was built at a time when trains were much smaller. This led to the recent blunder by the French train operator SNCF who ordered trains that were too large for the older parts of the network. We would totally never do anything like that, right?

Ultimately, this means we have to find space inside the trains themselves, which is difficult. On tube trains in the early twentieth century the motors were often at the same level as the passengers (those vents behind the cab), now they’re underneath which means more space inside.

Central London Railway (now Central Line) motor car 1903, Wikimedia Commons.

Another idea is the seat layout. New trains, such as the class 378 on the Overground and the new trains on the Metropolitan line, have longitudinal seating, basically the seats are like two benches running up the sides. This means less seating space, but more standing room, a solution Berlin, Paris, and New York were adopting in the 1920s. Furthermore, you can wonder merrily up and down the train between carriages.

Inside of a class 378 London Overground carriage, Wikimedia Commons.

This is really useful, because anyone who travels on trains in London knows that the middle of the train is always the fullest, but often the ends are empty. By allowing passengers to walk through the train, this problem is eased. While people might decry the loss of seating, and the seats mean you have to engage in a staring competition with the person opposite, during rush hour it makes all the difference. More people can get on and can move around the train far more easily. These are changes that tube trains are especially crying out for, because they’re the smallest of all the trains running in London and would gain the most.

Bigger tunnels

As I said, train size is limited by the space around the track. So why not just make it bigger? This is perhaps most applicable to the tubes, which are much smaller than their main-line counterparts. The answer is that it’s ludicrously expensive, but it is doable. In the 1920s the original 1890s City & South London tube was enlarged so it could be integrated with the rest of what became the Northern Line. This involved removing the tunnel segments, adding spacers, and then boring out a bit more of the tunnel before sticking the segments back in again. Initially they tried to run trains through while doing the work, but when a train hit a board in one of the tunnels and caused a collapse (thankfully the driver got the train out safely) they decided this wasn’t such a great idea. The line was closed and work went fairly rapidly. Unfortunately this means closing down a line and creates a lot of angry passengers who have to be provided with other means of travelling. But for a long term solution it is one London might have to think about sooner rather than later. If they could do it in the 1920s, we can probably do it now.

Robot drivers

Conveyed by robots? The city of tomorrow, today? Automatic trains aren’t new. The Victoria Line is run automatically and has been since the 1960s when for a bet they let the Queen loose at the controls of one of the trains. The “driver” in the cab is largely there for safety reasons and to push about three buttons. On the Docklands Light Railway the automatic trains are incredibly successful, and the lack of driver means children and bankers frequently fight each other to the death so they can get the front row seats. Why automatic train control hasn’t been extended is largely a question of trade union antipathy and the fear that the trains could develop a self-awareness that leads to a Star Trek style killing spree. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzuIijxHBh0 Ultimately, however, it means faster trains and trains that can be run closer together, creating a better service. Similar arguments can be applied to surface vehicles. Driverless cars are being increasingly tested, and if successful, would allow for a much more efficient flow of traffic.

Turn London into 1970s Stevenage

Stevenage, bizarrely, was something of a cause celebre in the 1970s over cycle provision with a superbly developed system of cycleways. Increasing cycling provision is vital in combating the rush hour. Bikes are small and efficient. The problem is the infrastructure to support them is usually pathetic. Better infrastructure is a well-worn argument; segregated cycle lanes from other traffic, the right of way to benefit bikes, etc. There are great alternative ideas, like sky cycle, a network of bike routes over railway lines which should be a serious consideration. In fact, in the nineteenth century there were some ideas proposed for elevated glass walkways over the street, an idea that could be adapted for cycle ways (cycling in the rain is grim, fix it with a glorious glass awning over the top Victorian Crystal Palace style). Other ideas could be turning London into a massive one-way system, freeing up one side of the road solely for bike use (London was turned into a giant one-way system for a day in 1962 to ease congestion during a tube strike). While a cycle lane effective takes space away from other vehicles, it does so in a way that is far more beneficial, economical, environmentally friendly, and at least 293% more awesome.

Silence of the trams

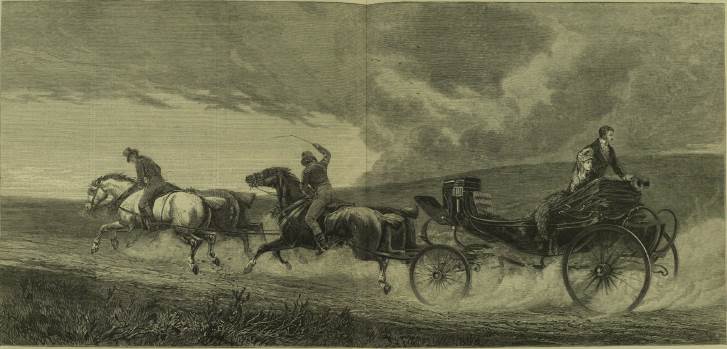

In 1952 London did something which at the time probably seemed like a good idea. With the benefit of hindsight though it was aggrieving short-sighted; they scrapped the tram system.While trams aren’t as flexible as buses, they are faster and have a much bigger capacity for passengers. Furthermore, they’re environmentally cleaner, given their electrical power source. For wide roadway with heavy traffic (such as Oxford Street) trams are ideal. We could even take a hint from 1920s north America, which operated ‘interurbans’.

Interurban tram, Wikimedia Commons.

These were like a cross between a tram and a train, operating a tram style service in the centre, then shooting off at high speed into the outer suburbs like a train (Cambridge features something a bit similar, the “guided busway”, though it’s a poor compromise, like a Dr Who episode featuring the Autons instead of the Daleks). While trams have returned to London, in Croydon, they really should be brought back into the centre. A lot of the former infrastructure remains, such as the Kingsway tram subway, and it would be great to see trams come back. If they’re good enough for almost every major European city, they’re probably good enough for London.

Abandoned Kingsway tram subway, Wikimedia commons.

Just get rid of the passengers?

Everything suggested above is expensive and inconvenient to do or only increases capacity by a marginal amount. But there is one thing that could be done; cut down the population of London (now, if you start screaming “end mass immigration” or something idiotically similar at this point (like they do in the comments of this mediocre Guardian article) please take this moment to walk out into the sea in your favourite concrete clothing – you’re missing the point here). London is a super-metropolis. It is not merely huge, but it is huge out of all relation to the rest of the UK. Greater London’s population is around 8 million, the next largest city, Birmingham, has a population of around 1 million. Trying to supply more transport to London, especially when we know more transport often encourages more people to travel, is effectively a self-defeating catch 22 at the moment. But if we could get rid of some of the passengers, that might make a bigger difference.

In twentieth century when the centre of London was severely overcrowded, the plan was to move people out of the centre into the developing suburbs where better quality housing was being built, into ‘garden cities’ like Letchworth or Welwyn, or the new towns, like Stevenage. This in turn encouraged businesses to move out into these areas to take advantage of that labour source, doubly relieving congestion in the centre of London. What London needs now is a decentralisation similar to what happened in those cases. If London could shift a couple of million people out into places like Birmingham (while concurrently giving those places the infrastructure to cope, ditch HS2, do this instead), the pressure on the London transport network would be relieved. The UK is suffering from a severe housing crisis, so here’s the basic solution; build lots and lots of cheap homes in those other cities, maybe even create a new town or two. Build up the transport networks too. Get a load of trams in there. Seriously, trams are awesome. No cable cars. Anyone suggests a cable car, have them shot. Encourage business to move into those areas. Pick a Wednesday and just scoop up Canary Wharf and stick it in Middlesbrough. The UK’s other cities benefit from increased housing and diversity of employment, London benefits as rents fall and congestion eases, everyone gets more trams. It’s a winner. It might seem like a bit of an overkill solution to get you a seat on the Piccadilly Line every morning, but of them all, this is the one that would make the most difference.

Or, you know, we could just build another cable car…