Being a historian is often being resigned to having a constant sense of déjà vu. This is doubly the case for anyone who has studied public transport, with ideas from over a century ago often being picked up and repackaged as the new big thing by policy makers. We may, however, have a new record for oldest revived policy: fresh from 1845, Jeremy Corbyn has suggested consulting on the use of women-only carriages in a bid to halt sexual harassment.

Women-only carriages (or ladies-only as they were typically called) remained part of the railways in Britain up until 1977. With 132 years’ worth of experience with them, their prospective reappearance is rather alarming. Then, as now, they were a knee-jerk reaction that created problems while failing to solve the immediate issue. Presented here, therefore, is the Pirate Omnibus guide to why this idea should be consigned back from whence it came, to a time when the main topic of conversation was repealing the Corn Laws, rather than whether Judge Rinder is better than Judge Judy (obviously, Judy would have him for breakfast).

In the nineteenth century the ladies-only carriage was a reflection of the gender-segregation of Victorian public life and the lack of autonomy women often had within it (an 1862 guide to using the railways had a section entitled ‘sending females’ by rail, which rather demonstrates popular attitudes), but also a reaction against numerous and recurring cases of sexual assault. The most infamous of these was the 1875 Colonel Baker case. Baker was a noted army officer, brother of explorer Samuel Baker, and friend of the Prince of Wales. He was also a sexual predator. While sat in a first-class compartment with 22 year old Rebecca Dickinson, Baker indecently assaulted her. Dickinson, unable to raise the alarm, climbed out of the window of the moving train, remaining half outside it with her foot on the foot board, and half inside as Baker clung on to her. She stayed like this for five miles as the train sped through the countryside until it finally came to a stop at the next station. Baker was arrested and eventually charged with indecent assault, dismissed from the army, and publicly disgraced. Dickinson was largely physically unharmed, but others were not so lucky, with some women suffering serious injuries or death.

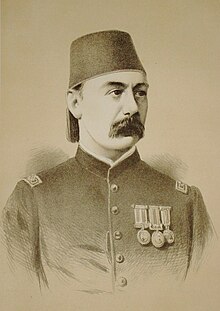

Colonel Valentine Baker, sexual predator in a fez, Wikipedia.

The Baker case highlighted that anyone could be a sexual predator, even the notionally ‘respectable’. As increasing numbers of women travelled by rail, the paternalistic reaction from railway executives (all exclusively male) was to separate off parts of the train in order to provide a safe space for women. Just as Corbyn’s suggestion is a reaction to the apparent increase in verbal and physically harassment on public transport (with sex offences rising by 32 per cent on London’s tube and train network to record levels last year), so it was over century before. The problem with this solution in the 19th Century, however, was simple. Almost everybody hated the idea.

The vast majority of women rejected ladies-only accommodation. When the Board of Trade surveyed usage in 1888, the Great Western pointed out that despite providing 1,060 ladies-only seats on its trains, only 248 women used them. In contrast, 5,141 women travelled in smoking compartments, despite women very rarely smoking in public. The majority of railway companies found that the accommodation simply wasn’t demanded. The Great Eastern had largely given up providing it, contending ‘ladies, for some reason, are unwilling to travel in compartments set aside wholly for them’.

There were multiple reasons for refusals to travel in the carriages. They became associated with clichéd old fashioned spinsters and were typically full of children (a common complaint by female passengers was that they were often used as mobile nurseries, with one correspondent pointing out that ‘women are, as a rule, very fond of their own children, but I for one draw the line at other people’s children […] when they behave like little monsters’). But more importantly, there were still serious concerns over safety. A ladies-only carriage was just as dangerous a space as any other carriage. Men still got into them and still occasionally attacked women within them. Lone female passengers chose to travel in carriages with other occupants, because, gender segregated or not, they were considerably safer than travelling in an empty ladies-only carriage.

Furthermore, ladies-only carriages encouraged a particularly unpleasant discourse that we today would consider ‘victim blaming’. An editorial from an 1875 newspaper, in the wake of a sexual assault, advocated ladies-only carriages with the argument:

‘[…] we must urge, in the interest of the public, men as well as women – for, after all, men have rights – that the ladies’ carriage experiment should be properly tried. It is incumbent upon the gentler sex not to lay themselves open to the gibes and sneers of the vulgar upon such a point as this, and the sooner they do so the better, or they will be the victims of retaliation.’

In short, travel in a ladies-only carriage or you deserve what you get. This kind of attitude is utterly unacceptable today, but ladies-only carriages act to reinforce it. The focus moves from the perpetrator to the victim, placing emphasis on the actions of any potential victim to avoid assault rather than dealing with the cause of the problem. This is a regular criticism of ladies-only carriages in the countries that still have them, such as in Brazil. Laura Bates, the founder of the (exceptional and well worth following) Everyday Sexism Project also highlighted this: ‘It seems to accept that the problem is inevitable, that men will harass women and that all we can do is contain them’.

Passengers waiting to board a women-only car on the Keio Line at Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, Wikipedia.

Aside from these fundamental problems, there are also practical ones. Many Victorian railways abandoned ladies-only carriages because they caused congestion in other parts of the train by preventing men and women travelling with men from using them. The Metropolitan Railway experimented with ladies-only compartments for only a year, during which there were legion complaints from male commuters saying the compartments were empty while the rest of the train was seriously overcrowded. That problem is even more apparent today. Furthermore, the carriages would complicate loading trains. Getting into any carriage on the tube is often difficult enough, expecting women to force their way to a specific part of the platform where the ladies-only carriage will arrive is ridiculous. Gender segregated carriages go against everything the last two centuries have told us about making railway travel safer and easier: open the train up as much as possible. The Underground’s new S-stock and the Overground’s new trains both allow passengers to walk the length of the train and see clearly along it. In the case of emergency, therefore, escape and help is much more likely. Finally, the notion of a binary gendered train is increasingly at odds with modern society, raising questions of whether they would discriminate against transgender and genderqueer individuals.

The women-only carriage idea is a non-starter. But it also ignores the reason that sexual harassment appears to be increasing: congestion. Trains and tubes are increasingly overcrowded. Counterintuitively, a seriously congested train is often an anonymous space. Attackers are lost in a crowd of people, it’s often difficult to see or react to them, and if someone is caught then they can often claim it was an accident. In today’s i there was an interview with a women who had been sexually assaulted on the tube, who explained: ‘I was on the Tube on the way to work. It was really crowded. There was a guy standing behind me – he was pressed up against me really close and then rubbed his erection against me.’ Relieving congestion by investing in larger trains and more frequent services makes these kinds of events less likely. Corbyn’s suggestion is to introduce women-only carriages on tubes after 10pm, which is unlikely to make much of a dent into the problem anyway. Not only is it an archaic policy, but it’s one that also misses the point.

Other suggestions are far more likely to help. The British Transport Police recently launched a campaign (Project Guardian) encouraging women to come forward and report sex crimes on public transport. The widespread use of smartphones means attackers can often be photographed or recorded, while CCTV also allows individuals to be identified. A greater staff presence on platforms and on trains is also key. The solution to solving harassment is not to remove women from a key part of everyday life, but provide the tools and assistance to prevent such events from occurring in the first place.

Ultimately, the women-only carriage is a relic of the past, and one that deserves to stay there. Perhaps the final word should go to a Victorian periodical, Funny Folks, reporting on the end of ladies-only carriages on the Metropolitan in 1875:

‘But as a rule, the carriages were empty. Courteous guards in vain strove to beguile maidens to avail themselves of the luxury; urgent porters recommended young mothers “a nice quiet corner for the baby” without effect. Sometimes in the interests of the company, they made a rush with a pretty girl’s luggage; but with a pout she would order it to be hauled out again, and, possibly out of mere dash and spirit, get into a smoking carriage. It would not do; the “ladies only” compartments had to be given up to “the mixture as before;” and man – proud man, got a lesson in the difficulties of legislating in the interests of the fair sex!’

He didn’t suggest it. It was suggested TO HIM by women, he only said it would be considered, which is the right answer. More on that here: http://www.jeremyforlabour.com/end_street_harassment

“Finally, the notion of a binary gendered train is increasingly at odds with modern society, raising questions of whether they would discriminate against transgender and genderqueer individuals.”

Interesting and very informative post, plus a very valid point imo that you make as quoted above. As part of the transgender community myself, I’d like to say thank you for taking the intelligent approach and not making fun of this issue as all too many people do.

I do find it ironic that many of the people who promote the idea of women-only carriages and gender separatism as a whole (e.g. trans exclusionary radical feminists) – purportedly in the interests of protecting women from assault – are the same ones who would seek to exclude one particular group of women who are statistically face very high risk of assault i.e. transgender women (particularly if they are pre-op or even non-op).

It’s a pity that Jeremy Corbyn did not seek to canvas the opinion of the trans and genderqueer communities on how such gender segregationist polices might impact upon us. Sadly, not every trans woman (even post-op) is accepted by society as looking it expects a woman to look and the likelihood that such a person might be turned away and prevented from using a woman-only carriage thus putting her in increased danger of attack would be quite likely if we were to adopt policies such as this.