Brighton, Wednesday, November 5th 1845. A crisis was breaking. Lady Adela Villiers, the seventeen year old daughter of the Earl and Countess of Jersey had disappeared. At 5pm that afternoon, Lady Adela had retired to her room to dress for dinner. But she then never appeared at the table. The house was searched, but no trace of her found. On further inquiries, it was discovered that at 5.15pm she had been seen traveling through the lodge gate and turned down St James’ Street with a small bag. The staff at the local railway station reported seeing no-one of her description. On Thursday morning there was still no information to her whereabouts. She had vanished.

The disappearance whipped up a furore in Brighton high society, The Satirist published a letter from one inhabitant

‘The comparative dullness (compared to days of yore) that has latterly pervaded this once right regal town has at length been dispelled – the spark of excitement is rekindled – scandal reigns supreme – or, more appropriately, in the words of the poet, Brighton “is itself again”.’

An answer to the mystery was soon forthcoming. Further inquiries at the railway station suggested a man, who had been holding a handkerchief against his face had bought tickets to London for himself and a woman who answered Lady Adela’s description. Then two letters were discovered from Lady Adela left in the house for her mother and her two sisters. On Thursday, at 4pm, Lady Adela’s brother, Captain Frederick Villiers, left London on an express train. His destination was Gretna Green, the village in Scotland famed as a destination for runaway English couples wanting to get married. A race was now on, could the Captain catch his sister?

The Lady Adela affair highlights the incredible impact the railways had on getting around Britain in the early nineteenth century. In 1836 express stage coaches could travel from London to Manchester (almost 200 miles) within eighteen hours, themselves a massive improvement on the three days it took in 1750. But with the developments following the opening of the Stockton and Darlington railway in 1825, the first public passenger railway in the world, these journey times would be slashed. In 1838 the London & Birmingham railway, the first intercity railway to connect London, could get you to Birmingham, 112.5 miles away, in 5 ½ hours.

Locomotive of the London & Birmingham Railway, from Wikimedia Commons.

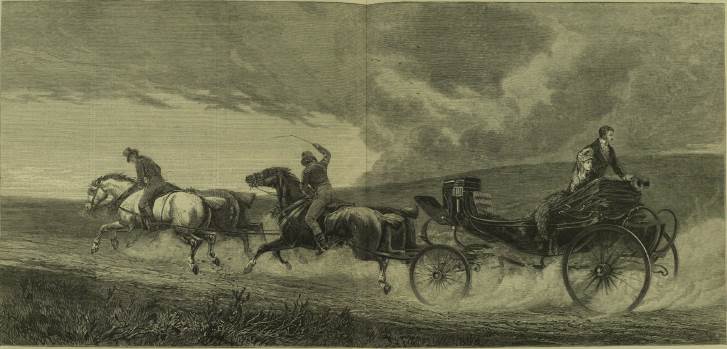

On Wednesday evening Lady Adela and her companion had reached London, and travelled straight to Euston station. Just before 9pm they were seen on the platform, the gentleman requesting a coupe for himself and the lady on the express train to York. By Thursday morning the pair were breakfasting at the York station of the North Midland railway, where Lady Adela’s ‘elegant’ appearance and manners apparently attracted the attention of fellow diners. They then took their places in the mail train (mail trains were typically the fastest express trains available) to Newcastle. At Newcastle they were met by the gentleman’s private coach, sent up the night before, which was attached to the mail train (private carriages could be placed on wagons and then affixed to trains). Unfortunately at this point the railway officials attempted to move the couple from their private coupe into a first class compartment with two other passengers. At this, the gentlemen, revealed to be Captain Ibbetson of the 11th Hussars, put up determined opposition, demanding a vacant carriage for Lady Adela and himself. Such was his manner and eloquence he got it, though now the fugitive couple could be readily identified. At 1pm the train reached Carlisle, the couple having covered around 400 miles within 19 hours. Here Captain Ibbetson’s carriage was detached, some post-horses put on, and the couple raced off towards Gretna Green. By 2.30pm they were married.

For Captain Villiers the race to catch his sister was over before it even began. At 4pm Villiers took an express from Euston to Wolverton (now part of Milton Keynes). There he was forced to take a third class parliamentary train (required by law and stopping at all stations) to York. Once there he tried to arrange a special engine for his own use (a charter train, whereby a whole train could be rented by an individual), but this proved impossible, so he was forced to wait until 9pm when the London mail train arrived to take him to Carlisle. He got there at 2pm on Friday, and by 4pm was in Gretna Green, a full day after his sister had departed the town for Edinburgh with her new husband. All Villiers could do was take the news of the marriage home with him. Lady Adela and Captain Ibbetson were re-married at St Pancras church in London later that year, affirming their somewhat dubious elopement in the eyes of her family who were forced to accept the arrangement and undertake some damage control.

The fact someone could get from the south coast of England to Scotland in under 24 hours emphasised the power of the railways and their technological marvel. It was a quantum leap on the situation just a decade or two earlier. But the speed of the railways was already being challenged. In 1848 a runaway couple from Cambridge were surprised to find themselves detained on their arrival at Liverpool Street station. The electric telegraph had been their undoing, their details being telegraphed from Cambridge to London the moment their elopement was discovered and beating them there. Runaway couples everywhere would have to take note…

Pingback: Your Interesting Links | Zen Mischief

Pingback: R.S.V.P: Répondez S’il Vous Plaît | Post Whistle

Pingback: Let them eat cake | The Pirate Omnibus