‘I don’t know whether these young people pay the same fares as other passengers, or whether they pay at all; but granted that they do, their fares only purchase for them the right to travel – not to torture all the passengers in the carriage they select.’

So wrote a passenger travelling from Edinburgh to Glasgow in 1869. His target, the so-called ‘itinerant musician’, or, to the reader of the 21st Century, the busker.

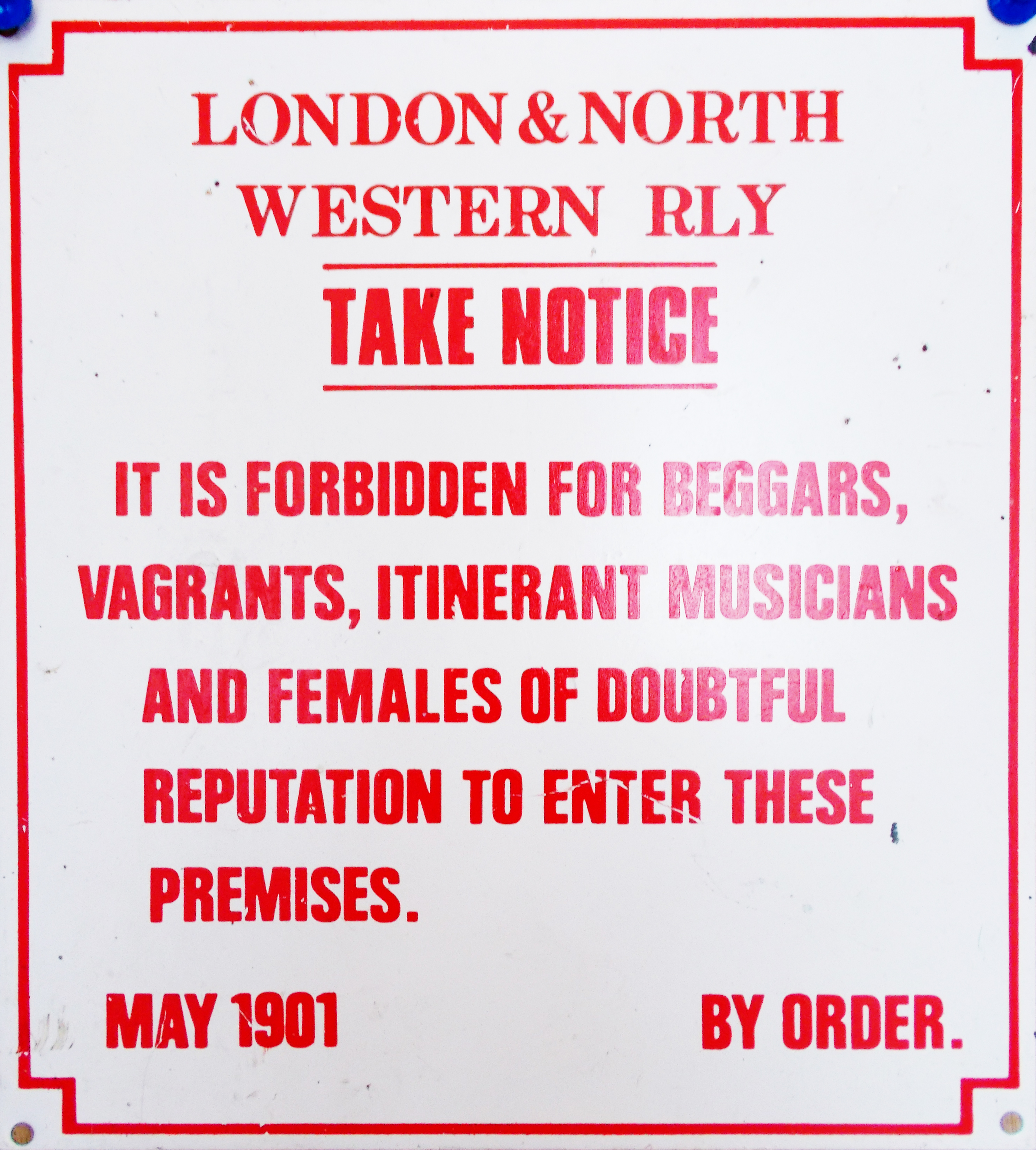

Busking is a fairly familiar sight to passengers on the modern railway, especially on the London Underground. In 2003 Transport for London altered its byelaws and made it legal for buskers to perform on special pitches, leading to a rapid infestation of Irish bands on the Circle line and this guy on his guitar. Certainly some are better than others, but to the railway companies of the 19th century buskers were a recurring nuisance. The LNWR thought them worthy of the same disdain as beggars, vagrants, and prostitutes.

Our Scottish passenger, writing under the pseudonym of An Observer, outlined his predicament to the Glasgow Herald. Having been treated to one busker on his first train, he was bewildered to find that on his second train yet another busker, equipped with a ‘stringed instrument’ , bundled himself into the passenger compartment. In the compartment were not only our passenger, but three men and a woman, all of whom were in funerary dress and in some distress, having just come from an internment. Not content to add to the troubles of the recently bereaved through his performance, the busker then managed to get into an argument with the occupants of the next compartment, a group of half-drunken sailors, the resulting ‘roaring, stamping, and stumbling’ of which lasted over an hour.

An Observer demanded that something should be done about these “musicians”, but it is clear that the busker was becoming an increasing presence on the railways, and especially in suburban London.

One busker in particular was apparently something of a presence in East London. In 1894 Mr Phillip Rigluth was called up in front of West Ham magistrates. According to a railway inspector, Rigluth was in the habit of taking a two-pence ticket and then travelling for hours around the Great Eastern Railway playing a concertina. In fact his concertina playing wasn’t what had landed him in court, rather he’d tried to get onto another train for which his ticket wasn’t valid, been caught by an inspector, and found himself fined 40 shillings by the magistrate for the pleasure. But the fine didn’t put Rigluth off, far from it.

In 1898 Dr F Greenwood was travelling home from Liverpool Street to Leyton on an evening train. At Globe Road station a busker jumped into the carriage and started playing a concertina. Greenwood demanded the man stop, but the busker was encouraged by some passengers of ‘the rougher sort’ to play as hard as he could. At the next station Greenwood managed to get hold of a guard, who ordered the busker to stop playing. Unfortunately for Greenwood as soon as the train left the station the busker started up again, as ‘the roughs encouraged him with words and coppers’. At Stratford Greenwood tried to get out to make a complaint, but was forcibly restrained by the other passengers as the busker fled the carriage. The busker’s escape was, however, short lived, as he was known to the railway company. It was, of course, Phillip Rigluth, who found himself back in West Ham Magistrates Court and this time was fined 14 shillings, or a ten day prison sentence if he defaulted.

Even this, however, did not dent our erstwhile busker’s enthusiasm. In 1900 he was caught again trying to get onto a train without a ticket, armed with his trusty concertina. Back in West Ham Magistrate’s Court for apparently the fourth time, Rigluth found himself fined 100 shillings (to put this in context, the average wage for a labourer at this time was around 20 – 25 shillings a week), the maximum penalty possible, with the threat of a month’s imprisonment if he defaulted.

Why was Rigluth so keen on busking? The information on him is scanty, but provides something of an explanation. Rigluth was an elderly man. He also claimed to be crippled. The combination of the two, he argued, meant that he was unable to work, so instead he eked out a living busking on the trains. Given he did so for at least six years, it seems a likely explanation, though slightly at odds with the account of his fleeing from the good Doctor two years previously. He was certainly a far cry from the ‘young people’ An Observer was so aggrieved by in 1869.

Whilst buskers were frequently complained about, from the concertina players to the ‘second rate vocalist’, they were a presence on the railways that was here to stay. They were typically male and usually found in the third class section of the trains. Indeed, An Observer remarked that such a commotion would never be allowed in first class, and Lloyds Weekly wryly commented that among some long-suffering passengers was the suspicion that certain of the railway companies permitted the nuisance in order to drive them into paying more to travel in the busker-free second and first class carriages. Certainly, there are references to the lower railway officials (porters and guards) doing little to prohibit busking, and only when the busker could be prosecuted for travelling without a ticket did the railway companies take effectual action.

Rumours of railway company conspiracy aside, the itinerant musician had become part of the social fabric of the railways, and they remain annoying and entertaining people as much in the 2010’s as they did in the 1860’s.

Pingback: History Carnival CXXV | historywomble

Pingback: Favorite History Reads of the Year | Erika Janik