In January 1868, Thomas Herron, also known as Viscount Ranelagh, was brought before Clerkenwell Magistrates Court. This noble Lord was being prosecuted for an action he thought hardly criminal; smoking on the Metropolitan Railway.

The Metropolitan Railway had opened in 1863 and was (along with its younger sister the District) the only railway in the country where smoking on board trains was prohibited (it had been exempted under the 1868 Regulation of Railways Act which obliged railways to offer smoking accommodation). The special conditions surrounding the Metropolitan, it being a short distance, high capacity underground railway, were argued by the Directors of the company to make it impractical to offer smoking compartments on trains.

Ranelagh put forward a guilty plea, but as he was being fined, decided to claim that he wasn’t a law-breaker after all, but rather pleaded guilty to save his time and wanted to offer some observations. Faced with this clear claim of innocence the Magistrate obliged him to remove his guilty plea and call evidence. The evidence did not help Ranelagh’s case. On the 20th December 1867 Ranelagh had been travelling on the 10.55pm train. According to the train’s guard, Ranelagh was smoking at Aldersgate Station (now Barbican) and he asked him to stop. At the next station, Farringdon, the guard once again found Ranelagh smoking. The guard again asked him to desist at which point Ranelagh ‘said there was no one there to annoy, and he would smoke and be damned to me’.

Lord Ranelagh in 1870 (Vanity Fair, Wikimedia Commons)

Ranelagh argued that when the no smoking regulations had been conceived smoking had been the exception, but now it was the rule. Most other railways offered smoking accommodation and as such the Metropolitan should permit smoking. The Magistrate decided that this wasn’t a particularly valid point of law and fined the erstwhile Lord 20 shillings. Ranelagh paid immediately.

This seems like a random incident, but the debate over smoking on the underground grew surprisingly large. In 1869 the MP for Dudley moved in the House of Commons that the Metropolitan be forced to provide smoking accommodation for each class of passenger, the House dividing in favour 175 to 167. However, the legislation was not immediately successful, and the company only offered smoking accommodation in 1874.

The subject was exceptionally divisive. A season ticket holder wrote angrily to The Times in 1870 to explain that despite the smoking ban he had

‘been much annoyed by the habit which now prevails of smoking at all the stations on the line, and in all the waiting rooms, refreshment-rooms and carriages. Pipes and cigars are puffed by all classes of passengers beneath the very noses of the railway officials, whose indifference makes us wonder at the fate of the passenger whose fine of 40 s is held up as a warning at the stations.’

A similar complaint was raised in 1868 by ‘John Bull’ who argued that

‘No one but a drunken man would attempt to smoke inside an omnibus, and if he did the conductor would very speedily eject him. But in a railway compartment, much more confined in space, smokers seem altogether to forget themselves…’

He added that smoking was practiced by gentlemen as well as ‘roughs’ and the staff did little to prevent it. ‘I have even seen a clergyman quietly smoking, and when I remonstrated with him he only laughed and said the guards all knew him’.

But the smoking lobby was a vociferous one. Writing in reply to ‘John Bull’, ‘M.J.B.’ contended that smoking compartments should be provided given that smoking was something to be grateful for ‘just after breakfast’ and ‘again in the evening after an abstinence of many hours’. He also added that the majority of passengers were actually smokers.

It was even thought that smoking on the Metropolitan was good for you. Henry Sheridan, the MP who moved the smoking bill, claimed in 1868

‘Medical men and others assert that smoking would counteract the effect of the sulphurous vapours which have been so complained of, and which are still as bad as ever, between the Edgware Road and Kings Cross stations…’

Of course, in reality, both smoking and the atmosphere of the steam run underground was liable to ruin your health, despite the claims of certain parties that it was like being in a spa.

The other problem was that the other railway companies who shared parts of the Metropolitan offered smoking accommodation. Trains from the Great Northern, Midland, and Great Western railways used stretches of the Metropolitan between Paddington and Moorgate. In 1871 Mr Arthur Bennet found himself in front of the Magistrates charged with smoking on the Metropolitan. However, Bennet had been riding in a Great Western train in the smoking compartment. When the train started at Ealing, smoking was allowed, but when it reached Paddington (and the Metropolitan), smoking was now prohibited. The gentlemen, despite his protestations that he was a Great Western customer and had nothing to do with the Metropolitan or their regulations, found himself fined ten shillings.

In 1874, however, the Metropolitan (because of the extensions it made beyond the tunnelled section that make up the northern part of the Circle Line) relented and smoking accommodation was allowed. One presumes Ranelagh’s reaction was something like this. The York Herald gleefully noted

‘The introduction of smoking carriages on the Metropolitan Railway under no other pressure than that of a feeling which operates so feebly upon most railway companies – consideration for the comfort of their passengers – is a step which merits the cordial approval of the public.’

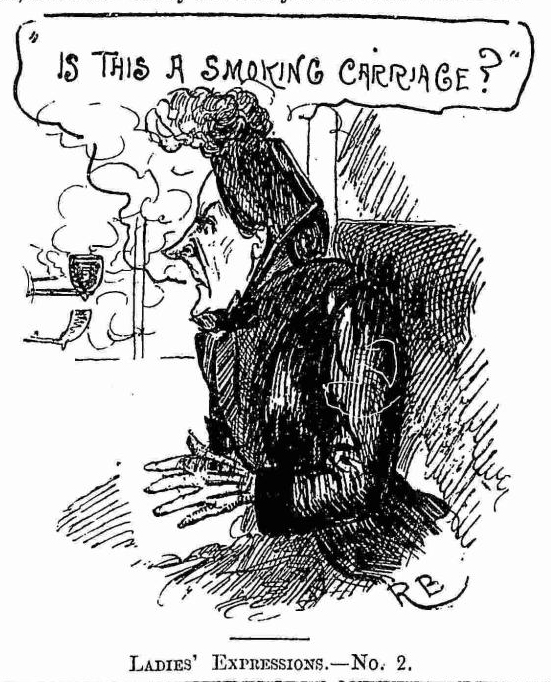

But the move bought consternation from non-smokers and especially those who complained about the impact for female passengers, who were also considered non-smokers (read more about this in ‘Ladies first’). Such complaints were soon brushed aside. Indeed, the history of smoking on London’s underground was one of ever increasing provision up to the Second World War.

On the Tube, where smoking had always been allowed on trains, by 1926 around sixty per cent of carriages were smokers. In that year, however, it was decided this was still not enough. Eighty per cent of carriages were thus given over to smokers, with non-smokers exiled to the first and last carriages of the trains. Rules which had banned smoking in the station lifts were also abolished, giving smokers leave to puff on cigarettes, cigars, and pipes anywhere they pleased. Concerns that this amounted to over-provision, and arguments that smokers were a minority in smoking carriages and hence aggrieved the other passengers were casually brushed aside. Smokers were the kings of the Underground.

But all things must come to an end. As we shall see in next month’s post, the smokers found themselves on the defensive after the Second World War. A story of marginalisation and tragedy followed, and in direct contrast to Ranelagh’s claim in 1868 that smoking was the rule, not the exception, the post-war story was exactly the opposite.