Last month we dealt with how the Underground became a smoker’s paradise. This month, we look at how it all fell apart. By 1926 around eighty per cent of carriages on the tube were smoking cars, and smokers had free reign to smoke in any part of the stations. But by 1959 there concerns from London Transport. Maybe, it was suggested, there was too much smoking accommodation.

In 1959 seventy per cent of carriages on the Underground were smoking cars. But Dr L G Norman, of the London Transport Executive, had made a somewhat startling discovery. Only thirty per cent of passengers smoked during their journeys. He had decided therefore, to reduce the smoking accommodation to fifty per cent of the carriages. Norman, however, was directly opposed to an outright ban.

In Norman’s opinion the public perception of smoking would probably lead to it being banned on the Underground, as it was in other countries, but for the moment London Transport refused to ‘play the grandmother’. When challenged by Reverend Little, the secretary of the National Association of Non-Smokers, that if only thirty per cent of passengers smoked, why hand over fifty per cent of the carriages, Norman noted that London Transport felt it better to ‘encourage, invite, and request, rather than order people about’. The language was conciliatory, but for smokers this was the beginning of the end.

In 1971 London Transport banned smoking on single deck buses and the bottom deck of double-deckers, it also decided to radically cut the amount of smoking accommodation on the tube, to only two cars on each train. They still, however, stopped short of a complete ban. A London Transport official noted ‘we believe our present proposals keep in step with public opinion and accord with our own observations of the proportion of people who smoke when travelling.’

From the 1st July 1984, however, London Transport’s observations had led them even further. Realising that the two smoking cars on each train were less used than the non-smoking cars they decided to ban smoking on the trains altogether. The reaction of some smokers was indignant. London Transport surveys suggested fifteen per cent of passengers opposed it. Mr Ivor Turnbull wrote to The Times protesting

‘Sir. How now may smokers soothe nerves tortured by the cola-drinking, hamburger-eating, paper-strewing, feet-on-seat-depositing, headphone-tintinnabulating habits of fellow passengers?’

A more serious problem was noted by Ms Linda Kirk who wrote to complain

‘On the London Underground last Saturday I attempted to persuade three youths who had lighted cigarettes in a non-smoking compartment that they should put them out, or move to a smoking car. When they proved uncooperative I asked a uniformed official on the platform at the next station to intervene. He refused to, saying he might well get stabbed. How is the complete ban on smoking in Underground trains – coming in force today – to be enforced?’

Others, however, expressed bewilderment that the ban was only on the trains. David Simpson, of the anti-smoking group ASH, noted his surprise that smoking had yet to be banned over the entire system, but hoped that in years to come the ban would soon be extended to stations as well.

For the most part the new ban seemed to be accepted fairly readily. The Times noted that on the first day ‘the price was paid in long faces, chewed fingernails, and an increase in peppermint consumption’. One passenger, however, managed to make legal history on September 14th 1984 when she became the first person to be prosecuted under the new rules. Miss Angela Williams was caught smoking by Chief Inspector Leithead of Scotland Yard on a train. Unfortunately, she apparently didn’t realise the Leithead was a police officer, resisted, and found herself being prosecuted not only for smoking, but assaulting a policeman and using abusive language.

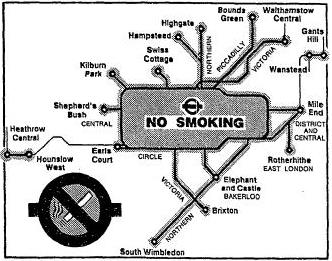

In December 1984 came a warning of the danger of a lack of a complete ban. A fire at Oxford Circus, probably caused by a cigarette or match, put the Victoria Line out of action for several weeks. From February 17th 1985 London Transport decided to ban smoking on all stations that were below or partially below ground. David Simpson, the Chairman of Ash, noted ‘This is a sign of the times. Smokers are becoming a small minority. All the dangers, which of course include fires, are now being recognized.’

But on the Monday after The Times reported that the ban was hardly noticeable.

‘Smokers puffed on cigarettes, pipes and cigars, often in the presence of London Regional Transport Staff, clearly unaware that the previous ban on smoking in trains had been extended to all parts of the system beyond ticket barriers. The only exceptions to the new ban are open-air suburban stations.’

On the 18th November 1987 someone, in violation of the smoking ban, dropped a lit match onto the escalator at Kings Cross station. At 7.30pm passengers reported a small fire on the Piccadilly line escalator. Around 7.40pm firefighters arrived to find a small fire and decided to fight it using a water jet. At 7.45pm, however, a flashover occurred filling the ticket hall with intense heat and smoke. Thirty-one people died.

Subsequent investigations found that several small fires had occurred under the escalator in the past, probably caused by dropped matches. These had all burned out, but on that night a fire had finally managed to take hold, and through the so-called trench effect, had been funnelled to devastating effect up the escalator. In the aftermath smoking was finally banned on all parts of the London Underground.

In the nineteenth century smokers had fought for the right to smoke on the underground. Ideas that smoking was good for your health abounded and its allowance from 1874 was viewed as a major benefit to the public. By the late 1980s, however, opinion was largely reversed. Smoking was anti-social and practised by a minority. Coupled with chronic underinvestment on the Underground it was also exceptionally dangerous. The smoking ban was soon followed on London’s buses in 1991 and on Network Southeast, the company running London’s commuter trains, in 1993.

Long gone were the days of Lord Ranelagh, who when caught smoking in 1867, had gruffly retorted to the guard of his train that ‘there was no one there to annoy, and he would smoke and be damned to me’

Pingback: History Carnival #128 « khronikos: the blog